My fascination with radio started at a very young age. It was already well established when — I’d guess I was in about second grade — I discovered an abandoned shortwave radio in my parents’ garage.

Breaking all sorts of rules, I plugged it in and began scanning the dial. I only had the built-in whip antenna (I wouldn’t get seriously knowledgeable about antenna design until about fifth grade) but I could still receive a number of stations in several languages. I could even pick up half of conversations over some kind of mobile phone system.

These radios used an incredibly dangerous design. One wire from the unpolarized plug was connected directly to the radio chassis, so touching the chassis was the same as sticking your finger in a light socket. The design relied for safety on the chassis being completely covered by the radio’s case, but one of the plastic knobs had broken and fallen off the front, and touching the exposed bare metal shaft connected you directly to the house current. I was usually barefoot on a concrete floor. It was a big jolt whenever I touched the bare metal. I had no idea at the time just how hazardous this was, but I lived to tell the tale. Years later, though, when I learned how these sets were wired and the risks I had taken, I got a bit weak in the knees.

Most of the stations were weak and staticy, but one reliably stood out: WWV from Fort Collins, Colorado. It is a US Government station that broadcasts a high-accuracy time signal. It has been broadcasting continuously for over a century.

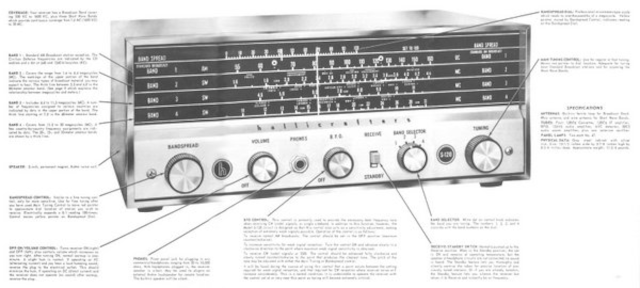

You might think that listening to a 24-hour-a-day time signal would get boring, but it truly fascinated me and listen I did, for hours on end. I eventually got an amateur (“ham”) radio license and started designing and building my own radios, but I kept that old Hallicrafters for a number of years, building in accessories like a beat-frequency oscillator so I could listen to morse code and single-sideband transmissions. When computers first became accessible to the tech-savvy masses, I was ready.

What reminded me of all this was unpacking the clock I had in the backyard of the mainland house. It’s one of those magical clocks that is always exactly on time, even though it uses a cheap mechanism powered by a single AA battery.

Keeping accurate time is remarkably challenging. You might think that being 99.9% accurate is pretty good, but that gives you an error of almost nine hours in the course of a year. This clock has maintained accuracy to within 1-2 seconds for many years. How do they do it? There’s a small radio receiver built into the mechanism that synchronizes with WWV. (Sellers often refer to these as “atomic” clocks, I suppose on the theory that they synchronize to WWV which uses clocks which, in turn, synchronize to atomic clocks.)

When I unpacked the clock, I went to set the time to my new middle-of-the-Pacific time zone, and discovered that the clock only has four buttons for setting the time, labeled ET, CT, MT, and PT (eastern, central, mountain, and pacific time, I assume). That’s “all” four time zones for the US (as long as you live in the contiguous 48 states). Of course, I didn’t think it would be likely to pick up WWV out here on the Great Ocean, but there is a sister station, WWVH, on the Hawaiian island of Kauai which should be within range. Alas, without being able to set the appropriate time zone, my clock is destined to always be off by a few time zones.

(I found instructions online for a “manual mode” for setting the clock. They start off odd: “Remove battery for 15 minutes and press the Manual Set Tab 20 times.” If the clock can’t receive or is programmed to ignore WWVH, then it might work, the clock just won’t be “atomic” anymore.)

—2p

addendum 2024-11-10

So far, it seems to be keeping pretty accurate time without apparently synchronizing to a time beacon.