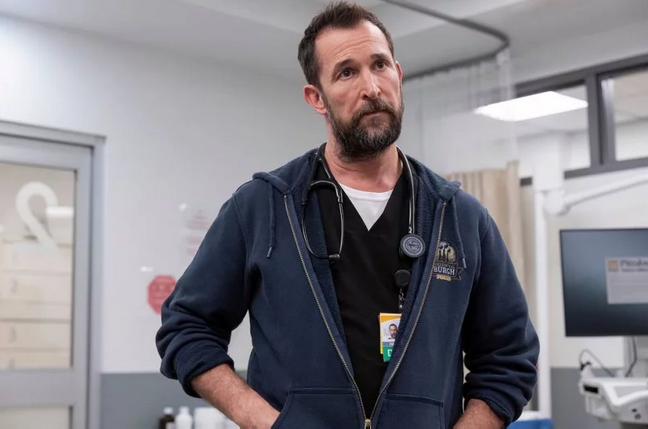

Warrick Page/Max

Warrick Page/Max

HA and I recently binge watched The Pitt, a television drama set in a big-city emergency department. It triggered some memories. Among the worst of these was of my urology rotation.

My first rotation as a medical student was in cardiothoracic surgery. It was intense, and there were stories that I have not yet told, but there was always a professional demeanor and if there was narcissism and hazing and abuse, it was always always in pursuit of better patient care. Misguided, occasionally, but everyone’s heart was in the right place. (See what I did there?)

My next rotation was… different. It was a urology service in a huge hospital system. Urology is a surgical service, and they didn’t let the medical students anywhere near the clinic end of things. When I went to medical school, students spent the first two years in the classroom (with some very token patient contact experiences because it was trendy for medical schools to claim they started clinical experiences on day one). I then spent three weeks on CT surgery, and on the first day of my fourth week ever being in a hospital, I was being asked questions that were very specifically about this new specialty that I had, at that point, been exposed to for only a couple of hours. I was very fresh and very new, and the attending physician asked about some bit of urological esoterica. I answered “I don’t know,” and so he asked the chief resident to explain it.

As soon as the attending left, the chief resident started screaming at me. “NEVER say ‘I don’t know.’ Make something up if you have to, guess, bullshit, but never say you don’t know.” I was stunned. If a third-year medical student on the first day of his second rotation is expected to “bullshit” rather than admit that he doesn’t know something, how is anyone expected to actually learn? I was old for a medical student — older, in fact, than the chief resident — and had owned my own company and had a lot of experience in worldly things and felt as though I’d just witnessed something horrific.

They were only getting started.

A day or two later, we were rounding and the chief presented a patient and proposed radical retropubic prostatectomy (an invasive surgical procedure with high morbidity) as treatment. The attending questioned this, and pointed out that the indications for this serious and risky intervention were marginal. “What, to you, is the determining factor to go with surgery?” he asked.

The chief resident paused, then answered “resident experience.” The team, even the attending, seemed momentarily stunned.

I thought it was a joke, but nobody laughed. Eventually, the attending said “well, okay I guess.”

Some days later, I found myself scrubbing in for the procedure. For a student, it was horrible. It is almost impossible to see anything useful as the procedure takes place deep in the pelvis and nobody was giving any consideration to the poor medical student pushed back from the table by the crush of bodies. The procedure dragged on for, ultimately, nine hours. The nursing staff, surgeons, and anesthesiologists all had backup and were able to take breaks, but nobody considered the lowly medical student. If I wasn’t allowed to say “I don’t know,” was it even vaguely likely that they’d be receptive to “can I take a break?” So I was on my feet the whole time, including when the chief resident severed a major artery.

It took many long minutes, maybe an hour, to get the artery located and tied off.

The patient got all the type-specific blood in our well-stocked big-city blood bank.

The patient then needed most of the O-negative blood, the type given when there is no type-specific blood available. After several more agonizing hours on the table, the patient eventually expired. All in the name of “resident experience.”

It was now well after midnight. Everyone just walked away. I’d been in the hospital for maybe fourteen hours, nine of them continuously standing, and had lived through a travesty. I shuffled to the parking lot in a daze, wondering if this whole medical school adventure had been a bad mistake.

As I was crossing the empty lobby of the hospital, I heard footsteps coming up behind me. I turned to find the attending anesthesiologist. He said we should talk. He found us a place to sit (bless him!) and proceeded to explain to me that what we just went through was not normal, not business as usual, that it should have been handled differently, that there would be consequences for the perpetrators but I would likely never know about them. He seemed quite concerned that I know that we had all just witnessed a horror. “This is not what should happen.”

In some significant ways, that anesthesiologist saved me. I very nearly went into anesthesiology as a specialty. We stayed in touch, and he was supportive of me through my next couple of rotations. The rest of the urology rotation went somewhat better, though I spent much of it resurrecting the Urology Department’s ancient computer systems (a service which earned me honors for the rotation).

A few months later, I was struggling with another difficult (but not horrific) surgical rotation along with the death of my godmother. It was midwinter. I was up rounding well before sunrise and, when I went home at all, got home well after dark. Remembering that anesthesiologist’s kindness was keeping me going during those hard days.

It was one such bleak, pre-dawn morning that I learned he had just been killed by a drunk driver.

Dark times.

—2p