A warning: most of my columns are fairly short; you should know in advance that this one isn’t.

I am a retired physician. Specifically, I was a board-certified family physician (that’s actually a medical specialty) as well as a psychiatrist. I was the first graduate from one of the first training programs in the country to offer both specialties together.

medicine doesn’t stop at the neck

I could go on and on about the ways that healthcare fails patients by persisting in the notion that there is a hard divide between the body and the mind. Descartes’ Error by António Damásio is a good starting point if you want to read more about the problem. Suffice to say that I saw the opportunity to address a lot of conditions that fell in the valley between the purely physiological and the realms of psychology. We dismiss so much serious illness as “all in your head” (like a brain tumor?) just because (a) the symptoms include behavioral or perceptive issues and (b) we don’t really have a good target for diagnosis or treatment.

I was focused on primary care until I did my psychiatry clerkship. It was then I realized that psychiatry was practicing in the way that I had imagined that medicine would work. In the VA hospital where I trained, it was common practice on the medical service to tune up a patient with a failing cirrhotic liver, and send him out with the exclamation that “he’ll live to drink again!” At the very same hospital on the psychiatric service, we’d sit with the patient for some time and discuss his drinking, what drove it, how aware he was of the implications of it for his health, and at least come up with a plan for addressing it (while, unfortunately, not taking steps to mitigate the medical issues that drinking was causing). I wanted to sit with patients and spend some time discussing their illnesses and how their physiologic processes interacted with their feelings, moods, and behaviors.

are you gonna talk about thyroids?

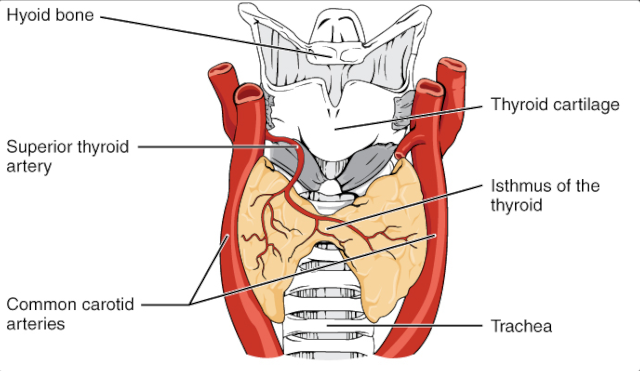

I’m getting to that. One place where there is a lot of interplay between mood, emotion, behavior, and physiology is in the endocrine system and perhaps the least well understood of that is the thyroid gland. The thyroid gland produces a class of hormones that has a profound effect on metabolic rate, energy level, skin and hair growth, weight, fatigue, heat/cold tolerance, and cognition.

So… does you or someone you know have trouble with fatigue? Weight gain? Depression? Brain fog? Guess what… that could all be due to a thyroid problem. You could probably find a doctor who would prescribe various kinds of thyroid hormones to try to fix the problem. The reality, though, is that there are many, many, many causes of fatigue, weight gain, brain fog, depressed mood, and the like. Thyroid is not high on the list of probable causes.

a patient walks into a clinic…

If a patient presents to a doctor complaining of some combination of sleep disturbance, lack of motivation, feelings of guilt and worthlessness, poor energy, problems with focus/concentration, change in appetite, and a general slowing down they are well on their way to a diagnosis of major depressive disorder, not hypothyroidism. Major depressive disorder (“depression”) is much more common than hypothyroidism and, as is said in the profession, “if you hear hoofbeats, it’s probably horses and not zebras.” A thorough doctor, however, will also do a thyroid test along with a few other zebra-spotting clinic studies while working up the depression. Seems simple enough, then: if the thyroid (and other) studies are normal, treat depression. If not, treat the thyroid condition.

I’m leaving out boatloads of important nuance here. If any of this is hitting home, please see a good medical practitioner. I’m painting a big picture, not trying to guide anyone’s diagnosis.

Pretty straightforward, so far. And, to be honest, in most cases it is.

before Prozac

Let’s take the wayback machine to a time not-too-many years ago before the advent of Prozac. If you were a healthcare provider and faced with a patient reporting the above symptoms, you had limited options. The antidepressants of the time were… challenging. So much so, that most primary care physicians were hesitant to use them, and for good reasons. They made patients sleepy and sedated, gave them dry mouth, urinary retention, dizziness, and lethargy. You had to take them — and suffer with those side effects — for four to six weeks before you could expect any benefit. As if that wasn’t bad enough, they were lethal in overdose. So often a depressed patient would feel the medications were just making things worse, and put the pills on the medicine cabinet shelf where they would wait like a loaded revolver for a really bad day and a suicidal impulse.

To further nuance things, in those days there wasn’t a simple and easy way to assess thyroid function.

So you’re faced with this probably depressed patient who probably cannot afford or is too stigmatized to see a psychiatrist. You might think “this could be thyroid disease” and you could prospectively try giving the patient an all-natural remedy (Armour Thyroid, desiccated pork thyroid produced by Armour and Company meat packers) or even the newfangled synthetic-but-physiological levothyroxine (“Synthroid”). And guess what? Some of the patients you treat this way will get better! Dramatically better! Why? Because (1) the placebo effect is powerful in the treatment of depression and/or (2) thyroid hormone is actually an antidepressant and/or (3) at least some of your “depressed” patients are actually hypothyroid. These are challenging, frustrating, and often heartrending cases and it doesn’t take too many successes to make you a true believer in the power of using thyroid hormone. Lacking other effective tools, you’re going to keep using one that you have seen actually work.

Alas, we had no way to monitor thyroid hormone dosing and probably overdosed more often than not. The symptoms of overdose don’t always show up right away, but are problematic and often not easily reversible (eyes protruding from their sockets, thinning of bones leading to osteoporosis and fractures, heart palpitations… almost all organ systems can be affected in some way). Soon, the overuse of thyroid hormone was recognized as a problem and the reaction was to pretty much stop using it to treat soft symptoms that might or might not be thyroid related.

after TSH

In the 1980’s we got widespread access to a new test that measured thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) with great sensitivity. TSH is a pro-hormone that the pituitary gland makes in response to low blood levels of thyroid hormone. Finally, there was a simple, easy, straightforward way to assess a patient’s thyroid status with a single, relatively inexpensive blood test. It was a great leap forward, but like many such leaps, some nuance was lost. I was at a conference where an endocrinologist gave a presentation where he said “thyroid need not be complicated. Get a TSH, and if the patient is in the normal range, nothing else need be done. Period.”

I wish.

This is true most of the time, but…

There are a number of excellent studies that show that small amounts of thyroid hormone can “augment” antidepressants in patients who don’t otherwise respond to them.

There are some studies and many anecdotes that show that patients can have a normal-range TSH but persistent symptoms of hypothyroidism that improve with adding thyroid hormone in doses that keep the TSH within normal range. It would be so much easier if we could always practice medicine with rules and dogma, but human physiology doggedly persists in demonstrating edge cases. Patients, also, having been misled by anecdotes or snake oil promotions will cling to the notion that the answer to their depression, fatigue, weight gain, and brain fog lies in ever-higher doses of exogenous thyroid hormone.

so, Doc, what about your thyroid?

Four weeks ago, we found some cancer cells in my thyroid. On Thursday, the surgeon removed the whole thing. My beloved thyroid (with its misbehaving cells) and some associated lymph nodes are currently sitting in a jar of formalin somewhere waiting for a pathologist to slice it up into little pieces to examine under a microscope. If all the bad cancerous cells are confined well within the removed thyroid tissue then HURRAY! I am effectively cured of the cancer.

but now you have no thyroid??!!??

Right. While there’s nothing like having an internal organ with a rich collection of regulation and feedback mechanisms to keep the correct levels of hormone in your system, in the case of thyroid we can do pretty well with just taking a levothyroxine tablet once each morning when you haven’t eaten for four hours and won’t eat for another hour. It means morning coffee in bed with HA will no longer be the first thing I do each morning; I’ll have to wake up a bit earlier for long enough to take that little pill.

What will be interesting is that we generally over replace thyroid in cases like mine. The theory is that if there are any malignant cells that escaped the surgery, we don’t want them stimulated by TSH that’s trying to tell my (missing) thyroid to make more hormone. The problems caused by long-term overdosing are considered less problematic than cancer.

I have lived my entire adult life with a constellation of symptoms that might be thyroid related but, in all honestly, probably are not: episodes of profound fatigue, chronically cold cold feet even when they’re in a tub of hot water, persistent weight gain even on a pretty severely calorie-restricted diet. I have been diagnosed with a mood disorder. My TSH has always been in the normal range, but higher than some experts think is appropriate (higher TSH implies lower thyroid function).

Levothyroxine has a very long half-life, and we have to pick a starting dose and stick with it for six weeks before re-checking TSH and adjusting the dose. So it might be a few months before we find the right dose, and I can discover if I’m really just fat, lazy, and morose by nature or if there was always a thin, vibrant, vivant me who was just held back by a lack of thyroid hormone.

Oh, and just to give the retrospectoscope its due, let’s just say that the thyroid hormone works wonders for me. Then I have to consider the possibility that, had I done thyroid supplementation years ago, it might have suppressed my TSH enough to have prevented the growth of these cancer cells in the first place. What a thought!

—2p